In early June 1919, suffragists from around the country traveled to Washington, D.C., to sit silently in the Senate chamber as men prepared to vote on the Susan B. Anthony Amendment for the third time in less than a year. The previous two attempts to pass the amendment had failed to meet the required two-thirds majority, first by two votes in October 1918 and then by one vote in February 1919. As temperatures crested 90 degrees on the afternoon of June 4, Senate opponents ranted about states’ rights and proposed various counter-amendments to hinder ratification. The women shifted anxiously in their seats. Finally, after hours of debate, the vote was called.

For the next several months, Park, Helen Hamilton Gardener, and their NAWSA colleagues vied with their nemesis, Alice Paul and her National Woman’s Party (NWP), to take credit for the congressional passage and to ensure that their respective versions of suffrage history would prevail. Since splitting in 1914, the NAWSA and the NWP (initially called the Congressional Union) had pursued contrasting paths to the vote. The NAWSA worked closely with President Woodrow Wilson and remained strictly nonpartisan. The NWP staged protests at the White House and elsewhere, and campaigned against Democrats (the party in power). For their increasingly bold tactics, NWP members were imprisoned in filthy, substandard facilities where they suffered multiple abuses, including forced feedings. Some members of Congress vowed to oppose the Nineteenth Amendment because NWP members picketed the commander-in-chief during a war; NAWSA leaders denounced the NWP upstarts, fearing their protests hindered the chances of congressional passage. After June 4, each organization claimed priority for what was, in retrospect, a shared victory brought about by the labors of generations of women.

A shared fear that the nation would ultimately grant the suffrage movement scant historical attention heightened the rivalry between the NWP and the NAWSA. If only one or two names would be remembered, each group wanted to ensure it was one of their own. The NAWSA and the NWP arranged competing celebrations and press events, including separate ceremonies, in August 1920, for Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby to sign the Nineteenth Amendment into law after it had been ratified by 36 states. To avoid entering this skirmish, Colby signed the historic document by himself at home.

Today, the names, faces, and organizational affiliations of these women are long forgotten. The suffrage centennial promises to reintroduce us to several of them, including Gardener, and to remind us of their triumphs and failures. The anniversary also provides an opportunity to reflect on the stories we tell about ourselves as a nation, and to consider whose contributions we remember and whose we don’t. No one understood the political importance of historical memory better than the leaders of NAWSA and the NWP, whose competing, yet equally limited, versions of history have shaped how the story of the Nineteenth Amendment has been told, to the extent that it has been told at all.

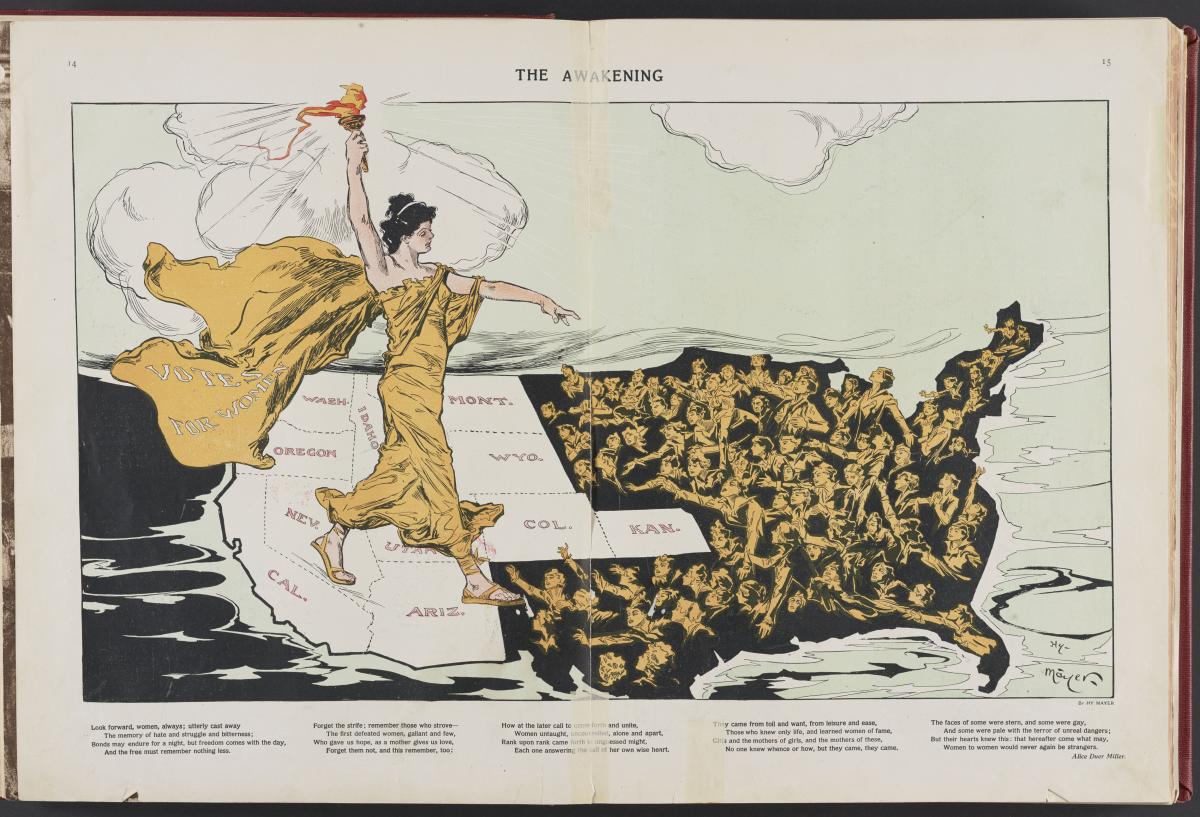

The Awakening by Henry Mayer, symbolizes the nation’s women’s desire for suffrage, coming from the western states, where women first had the right to vote. Printed in Puck, February 20, 1915.

—Library of Congress

Within days of congressional passage, NAWSA leaders secured a commitment from the Smithsonian to mount the first permanent exhibit on suffrage history—by which they meant NAWSA history. In various letters to Smithsonian officials, the women clarified that this exhibit must not mention in any way, shape, or form the NWP or Alice Paul. And it did not occur to them to include the contributions of the countless women who worked for the vote beyond NAWSA—especially women of color, who were generally shunned by both the NAWSA and the NWP.

The Smithsonian accepted the NAWSA artifacts—consisting of Susan B. Anthony’s portrait (which the museum had refused as of “no special interest” just the year before), Anthony’s red shawl, and a few other mementos—and arranged them on the small table on which Elizabeth Cady Stanton had drafted the Declaration of Sentiments in 1848. But the museum downplayed the significance of the small exhibit, titling it simply “An Important Epoch in American History.”

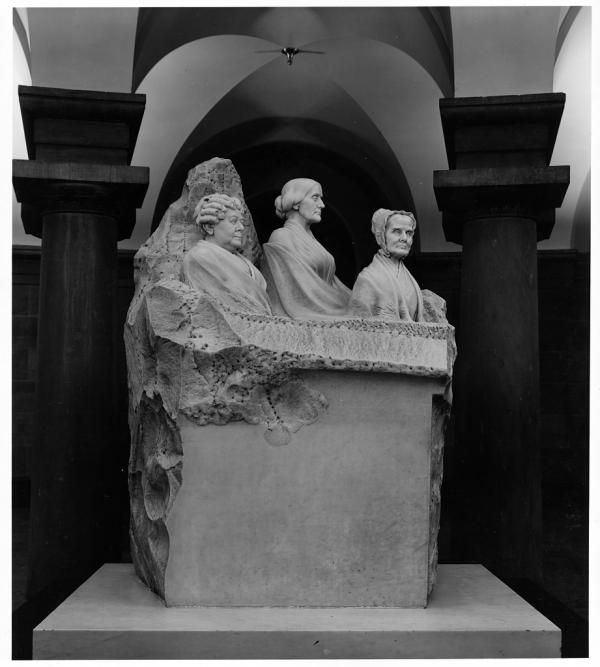

Incensed that NAWSA appeared to be winning the battle for memory, Alice Paul immediately began planning what she hoped would be an even more substantial testament to the suffrage movement. She commissioned Adelaide Johnson—who became known as the “sculptor of suffrage” after she crafted busts of Anthony, Stanton, and Lucretia Mott for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago—to recreate her sculptures of the three pioneers. Though Anthony and Stanton had led NAWSA, Paul believed that she was their rightful heir.

Paul aimed to place the busts in the Capitol Rotunda in celebration of the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. After suffering an improbable series of mishaps—from cracked marble to earthquakes to railroad strikes—Johnson completed her statue in Italy and shipped it back to America just in time for the elaborate ceremony Paul had organized.

But congressional approval proved trickier than Paul had anticipated, as Sandra Weber details in The Woman Suffrage Statue. In part, this was because Johnson decided to sculpt Anthony, Stanton, and Mott together in a single marble monument weighing more than seven tons. Such an enormous statue—called the Portrait Monument—complicated transportation and placement. Congressional leaders worried that the floor of the Rotunda could not support such a heavy statue. Others questioned the Portrait Monument’s artistic merit, dubbing it “Three Ladies in a Bathtub.”

Carrie Chapman Catt, the former president of NAWSA, added her own disapproval. She urged Congress to refuse the statue—not so much for its artistry but because she did not want Alice Paul to have occasion to gloat in the Capitol that the NWP had delivered the Nineteenth Amendment.

Finally, after the statue had languished just outside the Capitol for several days, the Joint Library Committee agreed to let the Portrait Monument be unveiled in the Rotunda. On February 15, 1921, the one hundred and first birthday of Susan B. Anthony, thousands of women crammed into the Rotunda for this historic occasion, and thousands more lined up outside. Various speakers declared the Portrait Monument a permanent reminder not only of women’s long struggle for the vote but also of their new status as equal citizens. As with NAWSA’s Smithsonian exhibit, however, the NWP ceremony presented a partisan version of suffrage history—which is to say that it skewed many people’s sense of the history it enshrined. One day after the Portrait Monument was publicly presented, congressional officials transferred it to a storage area underneath the Rotunda, known as the Crypt, where it remained for the next 76 years.

The marble statue of three suffragists—Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Lucretia Mott—by Adelaide Johnson, was kept in the Capitol crypt for 76 years.

For the past hundred years, the Smithsonian’s NAWSA exhibit and the Portrait Monument (which was moved back upstairs in 1997 after women’s groups raised the necessary funds) have provided the main national remembrances of the suffrage movement. Susan B. Anthony’s image appeared on a three-cent stamp in 1936, a fifty-cent stamp in 1955, and a silver dollar, produced in limited quantities, beginning in 1979. The Women’s Rights National Historical Park in Seneca Falls, New York, opened in 1980 to commemorate the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, the memory of which Stanton and Anthony carefully crafted in their multivolume History of Woman Suffrage and elsewhere, as the historian Lisa Tetrault has established. And, in 2016, President Barack Obama declared the Sewall-Belmont House, the long-term headquarters of the NWP, a national monument. But these tributes are a far cry from a complete history of the movement.

For starters, the truncated version of suffrage history centering on Anthony, Stanton, and Paul elides the larger complexities of the long struggle for the vote—which was, fundamentally, a battle for women’s autonomy—and glosses over the fact that the Nineteenth Amendment did not enfranchise all women. Black women in the South, Native American women, and other women of color remained disfranchised for years, if not decades, after 1920. Moreover, singling out only NAWSA and NWP leaders limits the story of suffrage to the efforts of white women, when women of color also made vital contributions to the cause.

Such limited commemorations have also failed to pierce our shared historical narratives, which still focus predominately on Founding Fathers, Civil War battles, and presidents. Following the federal government’s lead, history textbooks continue to give short shrift to suffrage (along with women’s history as a whole), presenting it in sidebars or optional units, as a 2017 report by the National Women’s History Museum documented. Neither the textbook version of suffrage history nor the NAWSA and NWP versions capture the breadth and depth of the movement or its increasingly significant lessons for us today.

Fortunately, as the 2020 suffrage centennial approaches, several national exhibitions have opened—or will soon open—that promise to upend, complicate, and diversify our understanding of the movement’s history.

The National Portrait Gallery’s stunning “Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence,” curated by Kate Clarke Lemay, opened on March 29. As the first national centennial exhibit, “Votes for Women” has set the bar high for subsequent commemorations. The exhibit takes as its point of departure the various origins of the movement—including but also displacing the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention—and foregrounds the many strands of activists and activism that led to the eventual ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. Significantly, the exhibit presents the amendment not as the terminus of women’s struggle for citizenship rights but as its midpoint. The final room reminds visitors that the Nineteenth Amendment did not become a reality for all women until the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, and it suggests, via video monitor, various ways in which women’s rights continue to be challenged.

The exhibit also highlights, in rare and beautiful portraits, several African-American women who worked for the vote along with other civil rights, through women’s clubs, church groups, and civic organizations, including the National Association of Colored Women, founded in 1896 and led by Mary Church Terrell. For those who look carefully, the exhibit advances a thoughtful argument about the challenges of centering those whose portraits, papers, and artifacts do not tend to be preserved in archives or museums.

On May 10, 2019, the National Archives opened “Rightfully Hers: American Women and the Vote,” which runs through January 2021 and is accompanied by a traveling exhibit entitled “One Half of the People: Advancing Equality for Women.” Curated by Corinne Porter, “Rightfully Hers” features the Archives’ collections of suffrage material—from countless petitions women sent to Congress to state ratification certificates to the Nineteenth Amendment itself. The exhibit tells the complicated story of women’s attempt to secure the vote before and after 1920, including a 1938 pamphlet documenting voting restrictions in the South, a 1946 affidavit from a Navajo Indian woman who was not allowed to register to vote, and the 2013 Supreme Court decision in Shelby v. Holder, which reversed provisions of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. A goal of the exhibit and related programming is to encourage all Americans to be “election ready,” even providing visitors the opportunity to register to vote on site.

To coincide with the one hundredth anniversary of congressional passage, the Library of Congress will open “Shall Not Be Denied: Women Fight for the Vote” on June 4. Drawing on the library’s vast manuscripts related to suffrage (many of which have recently been digitized), this exhibit will include a varied assortment of materials, from moving pictures to sheet music to foundational documents such as a rare printed version of the 1848 Declaration of Sentiments.

The U.S. Senate Historical Office has organized a series of talks and tours and will soon unveil an online exhibit of primary documents and explanatory essays analyzing the Nineteenth Amendment’s circuitous, 41-year-long path through the Senate. Under the auspices of the 2020 Women’s Vote Centennial Initiative, several public and private museums, historical sites, and partner groups have created a clearinghouse website, comprehensive calendar, and classroom resources.

Next year, the Smithsonian American History Museum will debut “Creating Icons: How We Remember Women’s Suffrage” on March 6. The centerpiece of the exhibit, curated by Lisa Kathleen Graddy, will be the Susan B. Anthony portrait acquired from NAWSA in 1919, along with material highlighting the NWP and other organizations. Displays will contrast the “famous” with the “forgotten” to press the question of what we remember and what we forget.

This impressive slate of national commemorations offers a stark contrast to the previous 99 years of relative silence. Each of these exciting projects links the Nineteenth Amendment to the longer, ongoing struggle for voting rights. Another shared goal is the commitment to showcase women beyond the triumvirate of Anthony, Stanton, and Paul. Each museum introduces visitors to fascinating women they may never have heard of before—from Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, who declared, in 1866, that it was impossible to separate racial discrimination from sex discrimination because “we are all bound up together,” to Zitkala-Sa, a member of the Sioux Nation, who helped lead the Society of American Indians to advocate for the citizenship rights of Native Americans (granted by Congress in 1924) to the tens of thousands of women whose names appear in the historical record only because they petitioned Congress for the right to vote.

One impetus for the plethora of suffrage centennial exhibits in Washington is the Smithsonian-wide American Women’s History Initiative, “Because of Herstory,” an outgrowth of the 2016 Congressional Commission Report on the American Museum of Women’s History. Another explanation for the newfound interest in women’s history at the national level is that, for the first time, many premier institutions—including the Smithsonian American History Museum, the Library of Congress, and the National Portrait Gallery—are led by women.

Beyond museum leadership, the record number of women in Congress have introduced several measures to commemorate the centennial. In 2017, Congress established the Women’s Suffrage Centennial Commission to “ensure a suitable observance of the centennial of the passage and ratification of the 19th Amendment.” Senators Marsha Blackburn and Kirsten Gillibrand, together with House counterparts Representatives Elise Stefanik and Brenda Lawrence, have even proposed the creation of a suffrage centennial coin.

But the larger question remains: To what extent will these centennial commemorations inspire a more comprehensive overhaul of our shared historical narratives? Will our textbooks, museums, and monuments soon equally include the experiences and contributions of women—not just Stanton, Anthony, and Paul—and present the history of women as vitally intertwined with the history of America as a whole?

After nearly a hundred years of national amnesia regarding the women’s suffrage movement (despite decades of scholarship by myriad historians), the ongoing and upcoming exhibits in Washington—along with many new books and state and local commemorations—suggest that we are now ready not only to remember women’s suffrage in a nuanced way that foregrounds race but also to fully incorporate women—of all backgrounds, races, and ethnicities—into our national narratives and into the centers of political power. Beyond the vote, exhibits, and statues, this is what the suffragists wanted all along.

Dr. Lumsden introduces our special issue with her prodigious historiography of suffrage and the media research across the past half-century. Decade by decade, she traces the scholarly research trends—and gaps—from the recovery efforts in the 1970s, through the cultural-historical and media coverage analyses in the 1980s, to intersectional approaches of black feminist scholars in the 1990s that challenged earlier accounts. As the century turned, scholars considered suffragists’ contributions to consumer culture and cast a critical eye on the visual rhetoric of spectacle in the form of parades and the White House pickets. By 2017, as the national centennial celebration commenced, three new books reflected on “the golden media effect” of elites with style, money and celebrity-like appeal who became engaged with the movement in its final decade. Much suffrage media research has been piecemeal, Lumsden argues. She calls for fresh comprehensive examinations of how U.S. suffrage print culture drew women into the public sphere and changed them both.

Dr. Lumsden introduces our special issue with her prodigious historiography of suffrage and the media research across the past half-century. Decade by decade, she traces the scholarly research trends—and gaps—from the recovery efforts in the 1970s, through the cultural-historical and media coverage analyses in the 1980s, to intersectional approaches of black feminist scholars in the 1990s that challenged earlier accounts. As the century turned, scholars considered suffragists’ contributions to consumer culture and cast a critical eye on the visual rhetoric of spectacle in the form of parades and the White House pickets. By 2017, as the national centennial celebration commenced, three new books reflected on “the golden media effect” of elites with style, money and celebrity-like appeal who became engaged with the movement in its final decade. Much suffrage media research has been piecemeal, Lumsden argues. She calls for fresh comprehensive examinations of how U.S. suffrage print culture drew women into the public sphere and changed them both.  Developing racialist themes more broadly, Dr. Grasso takes on the “differently radical” approaches to the suffrage question of the NAACP’s the Crisis, under the leadership of W.E.B. Du Bois, and of the Masses under editor Max Eastman. She underscores the “radicalized racialism” of the 1910s as manifested in these two magazines, one with a black readership, the other with a white one. They were as united in their support for women’s suffrage as they were divided by their distinct political imperatives. Grasso’s close look at the 1915 suffrage issues of both magazines illustrates their divergent perspectives on gender discrimination and disenfranchisement. “When examining suffrage media rhetoric,” Grasso writes, what’s important is to consider “race in gendered radicalism and gender in race radicalism.”

Developing racialist themes more broadly, Dr. Grasso takes on the “differently radical” approaches to the suffrage question of the NAACP’s the Crisis, under the leadership of W.E.B. Du Bois, and of the Masses under editor Max Eastman. She underscores the “radicalized racialism” of the 1910s as manifested in these two magazines, one with a black readership, the other with a white one. They were as united in their support for women’s suffrage as they were divided by their distinct political imperatives. Grasso’s close look at the 1915 suffrage issues of both magazines illustrates their divergent perspectives on gender discrimination and disenfranchisement. “When examining suffrage media rhetoric,” Grasso writes, what’s important is to consider “race in gendered radicalism and gender in race radicalism.”  Dr. Lewis acknowledges that the welcome avalanche of mainstream press coverage of New York’s suffrage hikers indeed subverted aspects of the suffragists’ purpose. For as the women walked the 170 miles from New York City to Albany in December 1912, the press often mocked and made light of their trek. She further contends that by portraying their pilgrimage as a journey of “adventurous, determined, and emotional heroines of an action-packed serial,” the press managed to publicize, represent and domesticate the meaning of the women’s public mobility in a way that made their activism seem less alarming and more intriguing.

Dr. Lewis acknowledges that the welcome avalanche of mainstream press coverage of New York’s suffrage hikers indeed subverted aspects of the suffragists’ purpose. For as the women walked the 170 miles from New York City to Albany in December 1912, the press often mocked and made light of their trek. She further contends that by portraying their pilgrimage as a journey of “adventurous, determined, and emotional heroines of an action-packed serial,” the press managed to publicize, represent and domesticate the meaning of the women’s public mobility in a way that made their activism seem less alarming and more intriguing. Finally, no new research on suffrage and the media would be complete without attention to the anti-suffragists, which Dr. Finneman provides with her work on local press coverage of the antis in the critical year of 1917, when their efforts neared defeat. Through the use of textual analysis and framing, and social movement theory, Finneman’s essay enhances the literature on press portrayals of counter-movements.

Finally, no new research on suffrage and the media would be complete without attention to the anti-suffragists, which Dr. Finneman provides with her work on local press coverage of the antis in the critical year of 1917, when their efforts neared defeat. Through the use of textual analysis and framing, and social movement theory, Finneman’s essay enhances the literature on press portrayals of counter-movements.  Dr. Easton-Flake begins to answer Lumsden’s call. She analyzes—in tandem for the first time—the literary works that appeared in the Revolution, the organ of the National Woman Suffrage Association, and the Women’s Journal, published by the American Woman Suffrage Association. Easton-Flake finds that the fiction and poems were an integral part of each journal’s polemics as the fiction and poems they published articulated and advocated their organization’s respective views of the new woman and the changes most needed for her advancement.

Dr. Easton-Flake begins to answer Lumsden’s call. She analyzes—in tandem for the first time—the literary works that appeared in the Revolution, the organ of the National Woman Suffrage Association, and the Women’s Journal, published by the American Woman Suffrage Association. Easton-Flake finds that the fiction and poems were an integral part of each journal’s polemics as the fiction and poems they published articulated and advocated their organization’s respective views of the new woman and the changes most needed for her advancement.  Dr. Unger’s analysis of the “big tent” yet “Janus-faced” suffrage arguments promoted by Bella La Follette in the pages of La Follette’s Magazine, demonstrates how, over two decades at the start of the twentieth century, La Follette deftly melded social justice and expediency arguments with the aim of attracting as diverse an array of suffrage supporters as possible. This included La Follette’s willingness to chide middle class white suffragists for their overt racism. While Unger concludes that the wide-ranging arguments of La Follette and others helped bring the Nineteenth Amendment to fruition, “they also reinforced lasting cultural, political, economic, ideological, and social differences between the sexes and among women.”

Dr. Unger’s analysis of the “big tent” yet “Janus-faced” suffrage arguments promoted by Bella La Follette in the pages of La Follette’s Magazine, demonstrates how, over two decades at the start of the twentieth century, La Follette deftly melded social justice and expediency arguments with the aim of attracting as diverse an array of suffrage supporters as possible. This included La Follette’s willingness to chide middle class white suffragists for their overt racism. While Unger concludes that the wide-ranging arguments of La Follette and others helped bring the Nineteenth Amendment to fruition, “they also reinforced lasting cultural, political, economic, ideological, and social differences between the sexes and among women.”