Interview: Rebecca Boggs Roberts on “Suffragists in Washington, DC: The 1913 Parade and the Fight for the Vote”

Rebecca Boggs Roberts’ book, Suffragists in Washington, DC: The 1913 Parade and the Fight for the Vote, is a concise, well-told and visually appealing narrative of the 1913 suffrage parade organized by Alice Paul, the activist known for employing militant tactics to push for women’s right to vote.

Boggs Roberts, a journalist, tour guide, and current program coordinator for Smithsonian Associates, explores the organizers behind the march, divisions among suffragists and how the event influenced the trajectory of the suffrage movement.

Alex Kane, a researcher for this website, spoke with the author on the phone about the parade organizers’ media strategy, how Boggs Roberts researched the book and much more.

Alex Kane: I wanted to ask about your research process. One thing that is always interesting to me is how authors of popular history books do their research. So, I was wondering if you could tell me what the most helpful sources were in constructing the story.

Rebecca Boggs Roberts: I came about this story in a sort of backwards way on the 90th anniversary of suffrage in 2010. I am on the board of a historic cemetery here in Washington and I was looking around to see if there were enough suffragists buried there to create a walking tour themed around suffrage. And there absolutely were. But what I mainly used for that research was obituaries, keyworded to suffrage. And what I kept finding was women who had been involved in this 1913 march. And I started with newspapers, but not necessarily the news section of newspapers. And obituaries are not a great source for women’s history, as The New York Times is discovering now with their new “Overlooked” project. But the advantage to writing 20th century history is that the newspaper coverage is very well preserved and searchable and keyworded, though coverage of women’s issues was dictated by male editors. I still use newspapers as my main source for this book, but I assume it is biased and the coverage is breathlessly sexist.

The articles are amazing in their phrase choice, the way they patronize these women. And then they were also known editorially to be for or against suffrage. So The New York Times for instance was unapologetically anti-suffrage. So, yes my main source was newspapers, but with an asterisk, understanding that these sources had their own point of view, which is probably a valuable less for anybody, but certainly when you’re talking about a controversial issue.

On top of that, there were letters. Letters in women’s history are often extremely valuable for all the reasons that newspaper history can be limited. But again, by the 20th century, with an issue this newsworthy, you don’t need to rely on letters so much. I think letters can be the only primary source for women’s history in 17th, 18th century writing. And then there are scrapbooks that a lot of the suffragists kept. The National Women’s Party maintains a collection, and they’re wonderful not necessarily in terms of the information they provide, but as a window into what women wanted to keep. And then there were the biographies of the women involved.

AK: You looked at newspapers and recognized the patriarchal bias behind their accounts of newsworthy events. How did you grapple with using information tainted by sexist bias?

RBR: You take that sexism as part of the story. It’s one more thing that these women were fighting against and having to strategize around. Obviously, from my own 21st century lens, there was some of it I could laugh at or read between the lines of. But, the very fact of their bias was part of the story. That’s one of the reasons that suffrage was so hard to come by and why it took so long.

AK: You have worked at as a journalist, and so I’m curious whether you think your journalistic background brought a particular lens to writing this sort of history that academic historians might not have.

RBR: I would say we have a different perspective, though one is not better or worse. But I think that any journalist, certainly any political journalist—I spent a long time as a science journalist and one of the things you’re constantly doing is making the human beings real human beings. The people are always more interesting than the stuff. And I think that history tends to forget that these are actual, real, thinking, breathing, complicated, frustrating humans.

A journalistic perspective helps you remember that this isn’t just about accomplishments and laws and dates and events, but it’s about the people that made those things happen. Any good contemporary journalist has to understand the human element as well. And there’s no reason not to have that be true, and with history even more so because the complicated, weird, stinky, strange, complicated side of humans gets lost in history.

AK: Pivoting to the book itself, can you explain for readers of this interview who might not have read your book, what the media strategy was for the suffragists behind the march and whether they were successful in using that strategy to generate a lot of press coverage.

RBR: I get asked a lot about the most surprising thing I learned researching this book. And my answer is always how incredibly savvy the press strategy was, and for that I give total credit to Alice Paul. I mean, she was so good at figuring out how to play a message, how to make sure the photos looked good in the paper, how to manage a set back to her own advantage. She really was just a master.

There were a couple of priorities before the parade. They really wanted it to be Pennsylvania Avenue. The symbolism of Pennsylvania Avenue, marching where the men marched—going literally from the Capitol to the White House—right down the corridors of federal power. That message was very important. So that was played up in the press a ton.

Then there was the strategy of including women from all over. Women came from all over the country to march, and there was a good list of who they were and what their hometown newspapers were covering and what sort of stories might be fed back to local newspapers around the country.

There was the visual element. So, how was everything going to play in a photograph? Not just the bands and the floats and everything of the parade itself, but the crazy pageant on the Treasury steps was entirely designed around how it was going to look in pictures. And we’re still impressed by those pictures. The armored “Columbia” standing there with her staff is still the cover of my book over a hundred years later because that image is so striking.

And the timing of the whole thing, to be the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, is a strategy that was borrowed for the Women’s March of 2017—it coincided with the inauguration of the president that these women didn’t vote for, to remind them from the very first minute in office that you ignore women’s voices at your peril. So, all of that strategy leading up to the march was very much part of the media plan, and how to get suffrage in the news when it had been languishing for a while, and how to keep it there long after the event.

But then of course there was a near riot. The march did not go as planned. It could have been an absolute disaster. The crowd was awful, and the police did nothing to stop the crowd, and in some cases, joined in with jeering and spitting and tripping the women. Not a single bit of that glorious day went the way it had been meticulously planned out. And I think where the real genius comes in is that Alice Paul recognized immediately that that was the best thing that could have happened. A perfect day would have been in the newspapers for a couple of days, and a near riot was going to keep suffrage in the newspapers for months. And so you can be the best media strategist in the world, but the real test is when it all goes pear shaped and you still make it work for you.

AK: It was like how water hoses and dogs being turned on black civil rights activists lead to newspapers devoting a lot of coverage to the issue.

RBR: Right. And then there were congressional hearings looking into the crowd, so that stayed in the news. The continued fallout from the day kept being newsworthy.

AK: You mentioned the striking photos, and your book has published a lot of them.

There’s more photos in your book when compared to others, and it’s not just one section, but photos are interspersed throughout. What went into your decision to emphasize the photos?

RBR: Yeah. So that’s another source we didn’t talk about. The photographs are a historical source and they are fantastic. The number of photographs and the interspersing them within the text is actually a model of the History Press [the company that published the book]. That was a mandate from my publisher. All their books are very photo heavy. They care a whole lot about the resolution and quality of photographs. They think through how the text on the images are going to match up from the very beginning. I pitched the History Press on purpose because the parade itself is such a visual story. You’re involved in suffrage history so you probably had seen a lot of those pictures before, but a lot of people really haven’t. And they’re amazing! I love those pictures, and I intentionally wanted this to be a photograph heavy narrative from the very beginning. So, it was a good match. History Press likes it that way. I wanted it that way. It’s a story told best that way.

AK: The parade was a pivotal moment in the history of the suffrage movement, but I don’t think a lot of people know that. So, lay out for me why the parade was such a pivotal moment in the women’s suffrage movement and how it influenced the trajectory of the movement going forward.

RBR: Yeah, I’ve thought a lot about this, and I think it was important for both short-term and long-term reasons.

I think it was a big exciting event that people could get involved with at a time when the movement was languishing. There’s that Harriet Stanton Blatch quote, that the American suffrage movement “appalled its opponents and bored its adherents.” It was in trouble. People weren’t excited about it, and the younger generation of American women weren’t involved. It was this fusty club lady cause.

So, it was a shot in the arm in terms of an event that people could get involved with and get excited about. So that mattered. And it mattered because it was a shot across the bow to the Wilson administration. One of the people that Wilson defeated was Teddy Roosevelt, who had a suffrage plank in his platform. It wouldn’t have been crazy for suffrage to have been supported in the 1912 presidential election. But Wilson didn’t support it and he won, so it was an opening shot to this new, self-proclaimed progressive administration.

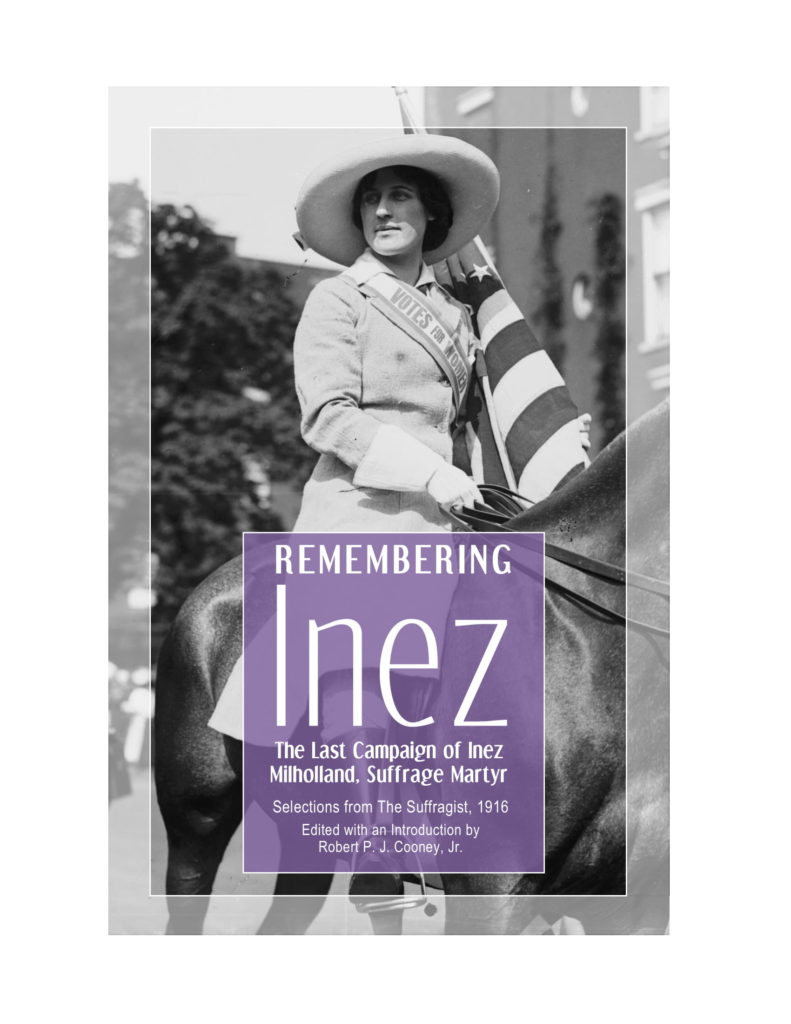

And it was a definite change of strategy, which gets overlooked in the pomp of the day itself. After the big split in the suffrage movement over the 15th Amendment and Reconstruction, two fractious groups got back together under the umbrella of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. They agreed to advance this state by state strategy, which wasn’t a crazy idea and had some success, but it was a very long, slow, expensive, hard to explain, hard to get people excited about strategy, and the march reintroduces the federal amendment as a strategy for the suffrage movement. It didn’t do away with the state by state strategy. They continued in parallel. But right behind Jane Burleson, who was the parade marshal, and Inez Miholland on her white horse with a big star on her forehead, there was a big banner that said, “We demand a constitutional amendment enfranchising women.” One sentence, one demand, subject, verb, object, incredibly declarative. And that banner then went with the National Women’s Party everywhere.

So it was very much a new announcement of revitalizing an old tactic. It wasn’t just a spectacular day. It was a shift in strategy.

AK: You mentioned Reconstruction and the 15th Amendment and race. I was intrigued by the role of Ida B. Wells, the great African-American journalist, in the march. Could you explain what her role was and what her role tells us about the role that race played in the parade.

RBR: Not just Ida B. Wells, but the Delta Sigma Theta sisters from Howard, who have their own interesting story.

Alice Paul was pretty young and green, and she was ambitious and she had some really fantastic ideas. But on the issue of how to handle black women who wanted to march, she fumbled, and she fumbled badly. When Ida B. Wells wanted to march with the Illinois delegation and Delta Sigma Theta wanted to march with the college group, Paul fretted that an integrated parade would mean that Southern marchers would drop out and settled on this very patronizing racist, “OK you can march but you have to march in the back” message. Ida B. Wells ignored that completely and marched with the Illinois delegation. And if you want symbolism there it is. She just went about doing exactly what she needed to do for her own priorities, and wherever she could work with white women she could, but if they stood in her way she worked around them.

Delta Sigma Theta split over marching and whether they’d accept the demand to march at the back. And that’s how that sorority was born. They are very proud of that legacy. I’ve been hearing from Delta sisters out of the woodwork since my book came out, and they have a sorority oral history that a lot of the women did not march at the back, that they jumped into the middle of the parade. I’ve tried to track down something more than an oral history source on that, but maybe there isn’t one. Regardless, it has been passed down for over a hundred years, that the Delta sisters jumped on in.

The history of the American women’s suffrage movement has a serious race problem. And there were times when it was overt, as when Susan B. Anthony tried to encourage Southern states to pass suffrage by saying that it would counteract the black vote. And there were times when it was more subtle—”you can march with us but you have to march in the back.” And there were black women’s suffrage organizations that did enormously important work. And there the ratification fight was another complete showcase for the racism inherent in the whole voting rights issue.

There is to be seen more scholarship on that issue. Elaine Weiss’ book touches on it with Tennessee, but I think as we approach this centennial in 2020, there’s going to be some really good work on the role of race in the suffrage movement. I look forward to it.

And of course, it’s about class too. Race and class are so hard to parse in this country. But the suffrage movement could also be accused of being classist. You can’t take a day to picket the White House if you work at a factory. And there were women who came to suffrage through labor activism who found it frustrating that it seemed to only appeal to women of a certain class. And I think all of the complicated, overlapping levels of that are one of the things I’m really looking forward to as more and more books come out on this topic.

AK: Last question: What do you think is the most important lesson that your book can impart?

RBR: So I read your Q and A with Elaine Weiss, and she and I draw the same conclusion from our research on the suffrage movement.

I mainly concentrated on the National Women’s Party, and they used more militant, in your face tactics. But I really don’t want people to take away the lesson that “some women sat in front of the White House and we got the vote, yay!” The slow and steady, color within the lines strategy is just as important, and neither would have succeeded without the other. And I think in every political movement the radical serves to make the moderate look more reasonable. You can say that the radicals need the moderates, because the moderates are the ones with their nose to the grindstone getting stuff done. But the moderates need the radicals too, because a member of Congress can say, “well, I won’t meet with that crazy Alice Paul, but I’ll sit down with that nice, polite Carrie Chapman Catt.” Both aspects—the people who were willing to throw some bombs, either literally or figuratively, and the people who were willing to do the slow and steady lobbying grassroots—make massive social change possible.