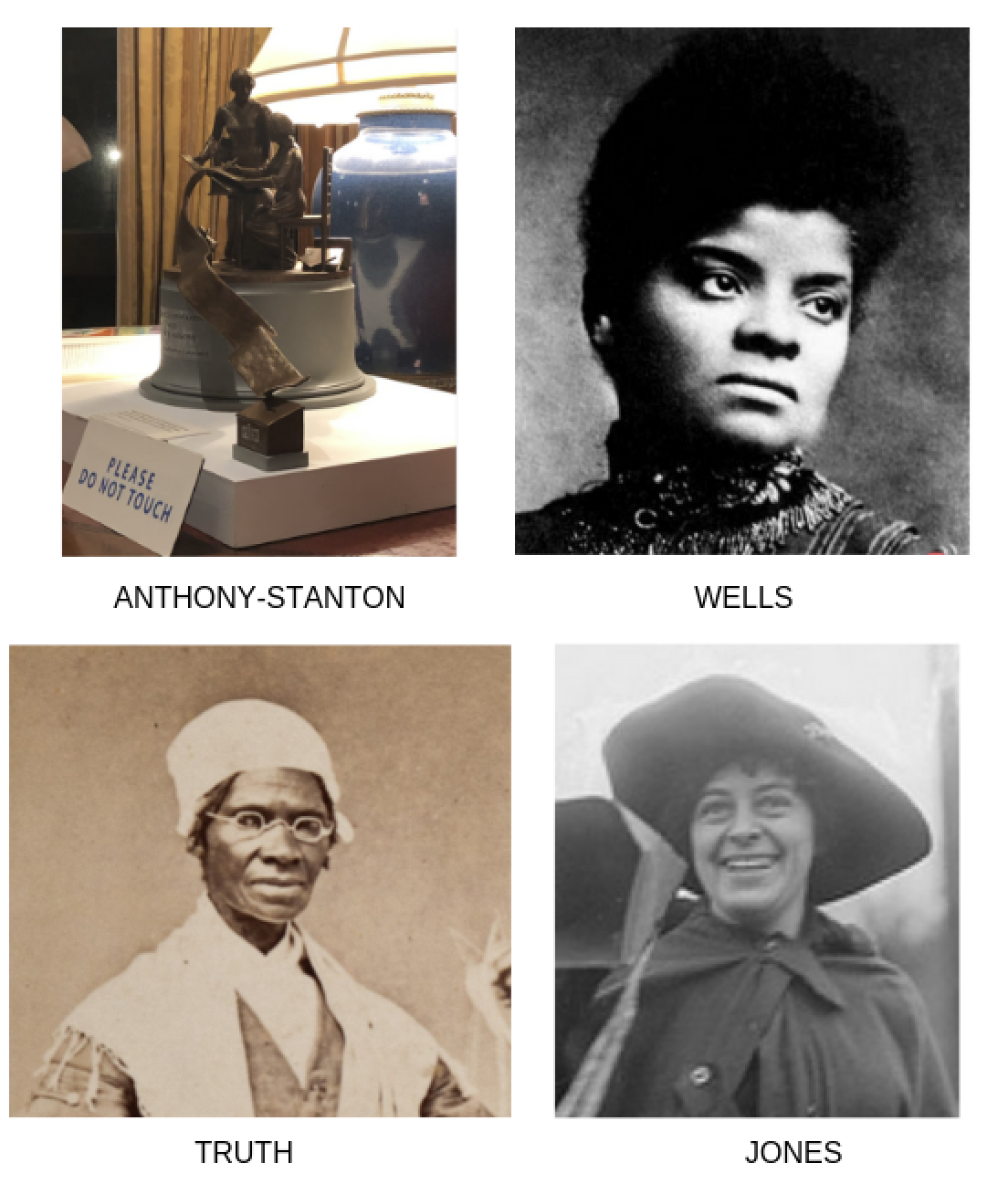

A bronze bust of Sojourner Truth, abolitionist and women’s rights advocate, sits in the Capitol Visitor Center’s Emancipation Hall. (Katherine Frey/The Washington Post)

Suffragists had a deep sense of history. In many ways they were our first women’s historians: taking a walk in the woods with Catt was like taking a course in suffrage history. But the story she offered at Juniper Ledge hints at why commemorating the upcoming centennial of women’s suffrage will be so fraught.

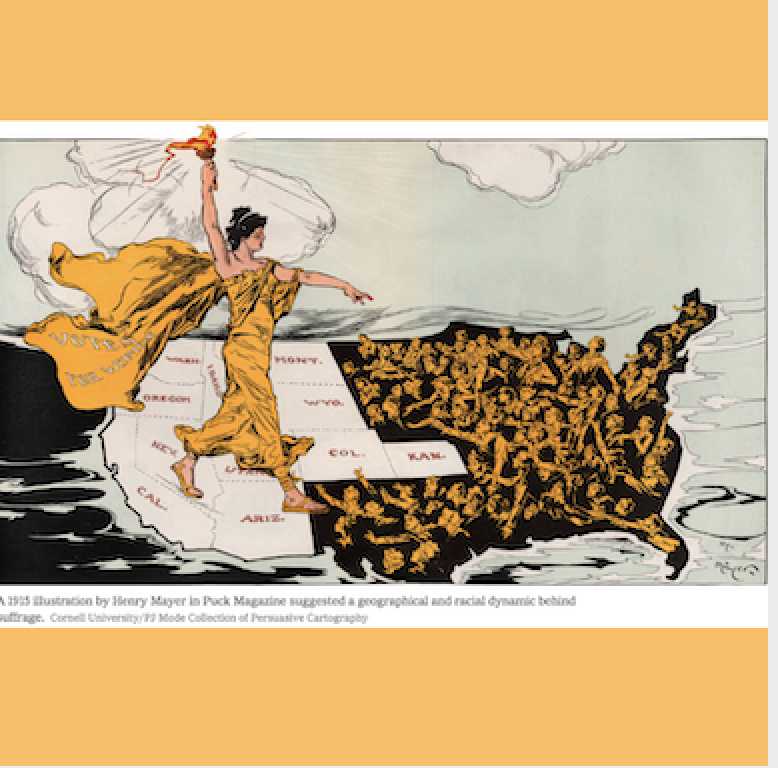

Consistent with the deep-seated prejudices held by most white suffragists, Catt included no plaques to commemorate the thousands of African American women who actively participated in the struggle. Regional chauvinism was an issue as well: All the domestic suffragists were from the East Coast, with New York State vastly overrepresented. There was no one from California or the West, nor anyone from the South, unless you counted the Grimké sisters who left their native South Carolina to settle in Philadelphia and later New Jersey.

For too long, the history of how women won the right to vote has closely paralleled Catt’s suffrage forest: top-heavy and dominated by a few iconic leaders, all white and native-born. Moving away from that outdated approach reveals a broader, more diverse suffrage history waiting to be told, one that shifts the frame of reference away from the national leadership to highlight the women — and occasionally men — who made women’s suffrage happen through actions large and small, courageous and quirky, in states and communities across the nation. Suffrage activists campaigned in church parlors and the halls of Congress, but also in graveyards on the outskirts of college campuses, on the steps of the Treasury building and even on top of Mount Rainier.

African American women are at the center of this newly reconfigured suffrage history. Their intersectional vision linking race, class and gender stands in stark contrast to the views of many white suffragists, who tended to view the vote primarily through the lens of gender. African American women brought a wider perspective to the struggle from the very start. In 1832 Maria W. Stewart was the first American woman, black or white, to speak in public about politics and women’s rights before a mixed (or in the terminology of the time, “promiscuous”) gathering that included men and women of both races.

Over the next half-century, black suffragists such as Mary Church Terrell, Sojourner Truth, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Fannie Barrier Williams and Ida B. Wells-Barnett similarly refused to separate race from sex, insisting that their voices be heard in both movements that affected their lives. When Harper addressed a suffrage gathering in 1866, she reminded the audience, “We are all bound up together in one great bundle of humanity.” White suffragists ignored Harper’s message, but it speaks powerfully to us today.

The voices of African American suffragists are not the only ones that have been overlooked. Thousands of unheralded women representing a vibrant mix of regions, races and generations came together in one of the most significant moments of political mobilization in all of American history. Women who had never before participated in politics suddenly found themselves doing things they never would have thought possible: filing lawsuits, holding public protests, collecting signatures, lobbying members of Congress, marching and even risking arrest and imprisonment. Claiborne Catlin, a 32-year-old widow, rode a horse, solo, for four months across Massachusetts to drum up support for the cause.

Participating in the suffrage campaign provided women like Catlin with the kind of exhilaration and camaraderie often described by men in times of war. Many were foot soldiers — not everyone wants to be a leader like Catt or Alice Paul — but their contributions made a difference to the movement’s ultimate success. Their hard-fought victory represented a breakthrough for American women as well as a major step forward for American democracy.

What the suffragists of the 19th and early 20th century understood was that the struggle for women’s rights did not end with the 19th Amendment. There is a direct line from the spectacles of the suffrage campaign to the sea of pink pussy hats worn at the Women’s Marches held across the country, and around the world, in January 2017 to protest the inauguration of Donald Trump. The playbook that suffragists pioneered, right down to their distinctive colors and seizure of symbolic public spaces, reminds us that history can be both a guide and an inspiration.

The wave of female candidates in last year’s midterm elections and the unprecedented numbers of women who have already declared they are running for president in 2020 are another clear legacy. The diversity of these candidates — black, Latina, Muslim, Asian, Jewish — may seem like an aberration when set against the all-white history of suffrage that historians used to tell. But these breakthroughs directly build on the demands for fair and equitable access to the political realm that were central to the struggle to win the right to vote in the first place.

The strategies and lessons of the suffrage campaign provide a clear blueprint for the mobilization of women today: Embrace a broad definition of political activism which goes beyond electoral politics but still encourages women to change the political system from within. Deploy public spectacle and mass demonstrations to bring women (and men) into public spaces. Use popular culture and new forms of media to get the word out, but don’t forget older techniques like lobbying and grass-roots organizing. Mobilize coalitions and alliances that cross race and class and draw on the energies of multiple, overlapping generations. Remember that feminism is a cumulative effort, not a one-off event, and it will always be necessary. All of these insights are as relevant today as they were at the height of suffrage mobilization in the 1910s.

The upcoming centennial of the 19th Amendment is a tremendous opportunity to root the dialogue about women’s roles in politics and public life in a more expansive, more representative history. Who should we nominate for Catt’s more inclusive suffrage forest? Emmeline Wells, the Mormon wife in a polygamist marriage who saw no conflict between women’s rights and her faith? Nina Allender, the artist who gave up her career to become a political cartoonist? Wells-Barnett, the African American activist who refused to march in a segregated parade? These women are just three of the fresh suffrage stories waiting to be told.