An exhibit at the Women’s National Republican Club in New York tells the story.

A century ago next year, after several decades of resilient activism, women finally earned the right to vote. And in New York State, the final push for suffrage was launched in 1910 by one-woman juggernaut Henrietta Wells Livermore, who also founded the Women’s National Republican Club in 1921.

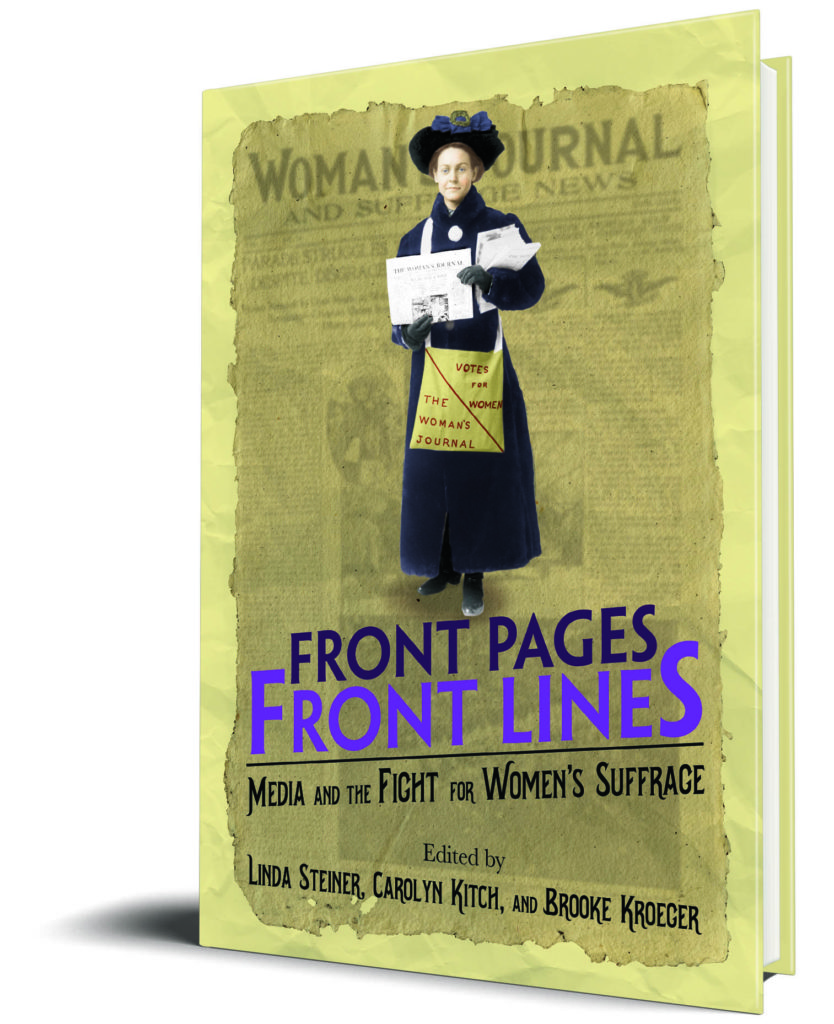

This year, to commemorate the historic achievement, the club is featuring an exhibit titled “Women’s Suffrage and the Founding of The Women’s National Republican Club” in its Manhattan headquarters. The exhibit highlights the suffrage movement, the club’s role in educating women about politics and their newly gained right, and relics from the era, including a letter from President Calvin Coolidge.

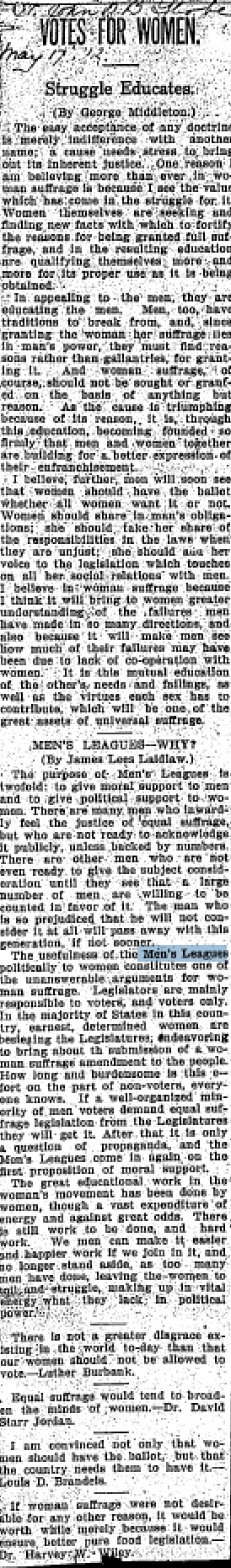

On February 14, 1910, twelve women met at Livermore’s home to revitalize the suffrage movement in New York State, and suffrage for New York’s women was passed in a statewide referendum in November 1917. To inform women of their newly gained right and the subjects they’d be voting on, she founded the Women’s National Republican Club in New York City in 1921. Today, it’s the oldest national club for Republican women in the country.

The clubhouse itself is the third home of the club, built to accommodate its growing membership, and is located in the heart of Manhattan at the site of Andrew Carnegie’s former home at 3 West 51st Street. The building’s interior is distinguished and regal, and it hosts gala dinners, awards ceremonies, and other events for its members. One of its committees is the Henrietta Wells Livermore School of Politics, which continues to organize volunteers for political campaigns and sponsors political-education seminars and lectures.

“Livermore decided that women needed to be educated so they could vote,” Judy McGrath, the exhibit curator, tells me as she guides me through it. “She was disappointed that there was very low female turnout in the first election that women could vote in, so she wanted to create a place where women could meet other women and become educated on the matters they’d be voting on.”

The exhibit details the club’s history and the lives of its founders, who also include Pauline Sabin and Ruth Baker Pratt. Ruth Baker Pratt was the first female representative to be elected from New York (in 1928), and she said on Election Night that she “did not run as a woman but as a citizen.” Pauline Sabin was the first woman representative to the Republican National Committee and served as a delegate to two Republican National Conventions. She also played a significant role in the repeal of Prohibition.

The exhibit also includes many relics, including a letter from GOP president Calvin Coolidge to the club commemorating its opening in 1924 and a 1902 letter from Susan B. Anthony. Coolidge was an ardent supporter of suffrage at a time when it was unpopular. Usually a walker of the party line, he went against his party’s orthodoxy, noting that women uniquely look to the future and “think of conditions not only for themselves but for their posterity.”

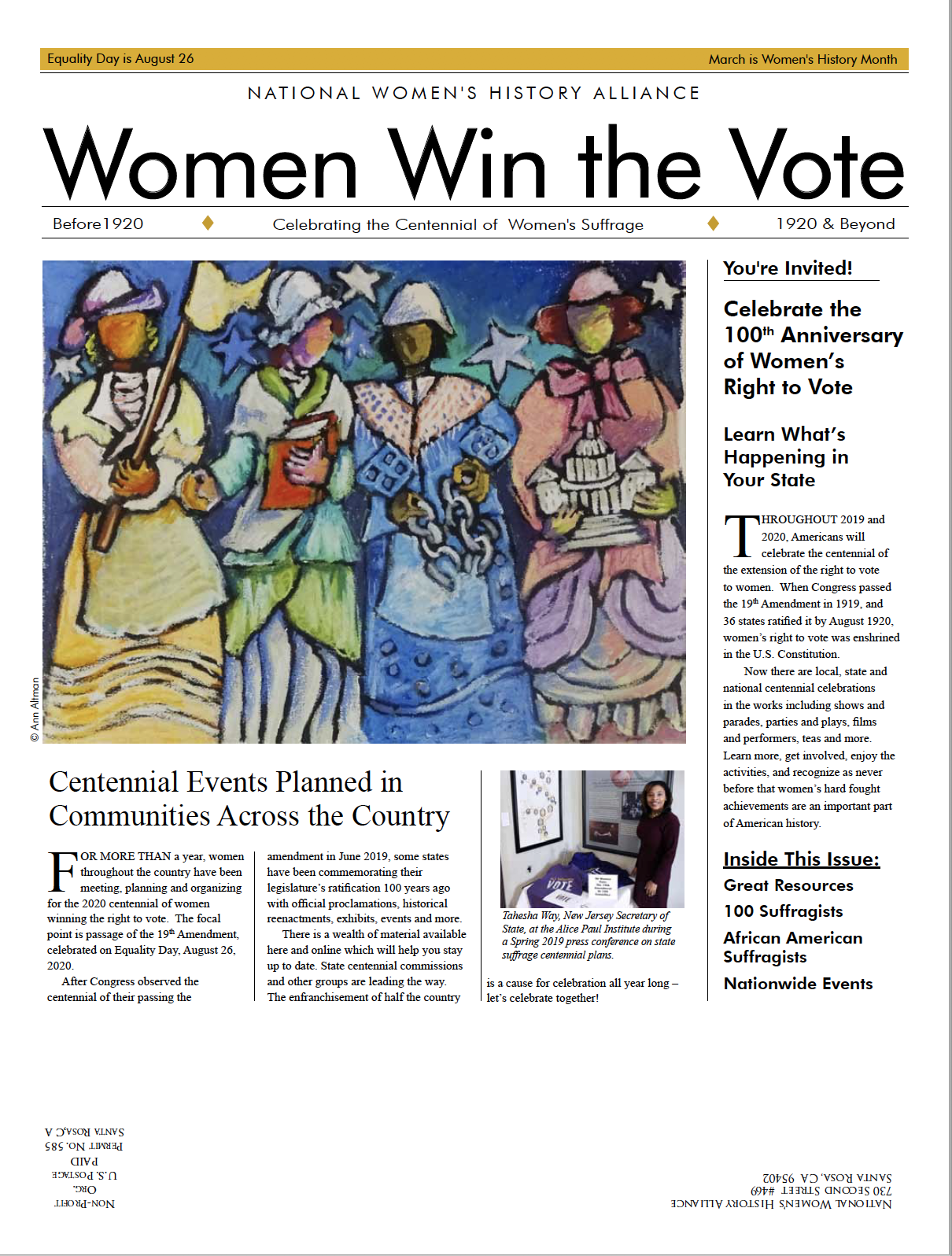

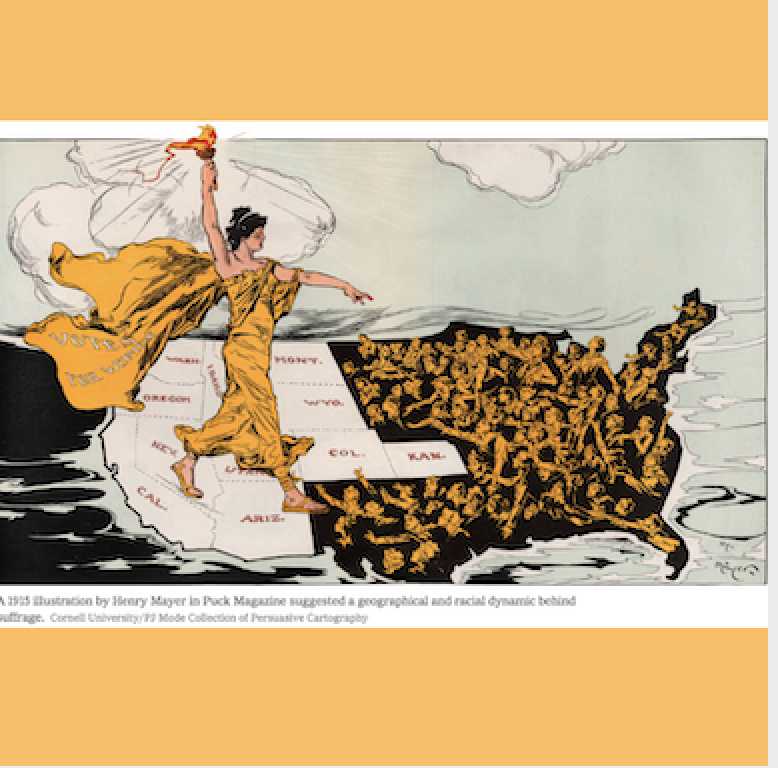

Eventually, the Republican party became the first major party to advocate equal rights for women, and it wasn’t until the Republicans gained control of Congress in 1919 — after Democrats had defeated the 19th amendment four times — that the amendment passed. Twenty-six of the 36 states that ratified it had Republican legislatures.

Maritza Bolano, a chairwoman on the Suffragette Committee and the editor of a forthcoming book detailing the suffrage movement and the founding of the club, emphasizes the importance of the Republican party’s role in suffrage. “The Republican party was the leader in women’s rights, as it had been the leader in abolition from Lincoln. The party leaders welcomed women and wanted women to participate.”

The exhibit is open to club members and their guests, and Bolano tells me groups are encouraged to contact the club and arrange to view it. “It’s important that young people, especially, learn from this exhibit.”